- 1 1. What Is Java wait()? (Understand the Core Idea Fast)

- 2 2. Correct Usage of wait() (Understand with Code Examples)

- 3 3. The Difference Between wait and sleep (The Core Search Intent)

- 4 4. Advanced wait Knowledge (Must-Know for Safe Usage)

- 5 5. Common Errors and How to Fix Them

- 6 6. Modern Alternatives in Java (Practical Perspective)

- 7 7. Summary (Final Notes for Beginners)

- 8 FAQ

- 8.1 Q1. Is wait a method of the Thread class?

- 8.2 Q2. Can I use wait without synchronized?

- 8.3 Q3. Which should I use: notify or notifyAll?

- 8.4 Q4. Can wait be used with a timeout?

- 8.5 Q5. Why use while instead of if?

- 8.6 Q6. Is wait commonly used in modern production code?

- 8.7 Q7. Can I replace it with sleep?

1. What Is Java wait()? (Understand the Core Idea Fast)

java wait refers to a method used to temporarily pause a thread (a flow of execution) and wait for a notification from another thread.

It’s used in multithreading (running multiple tasks concurrently) to perform coordinated control between threads.

The key point is that wait() is not “just waiting for time to pass.”

Until another thread calls notify() or notifyAll(), the target thread remains in the waiting state (WAITING).

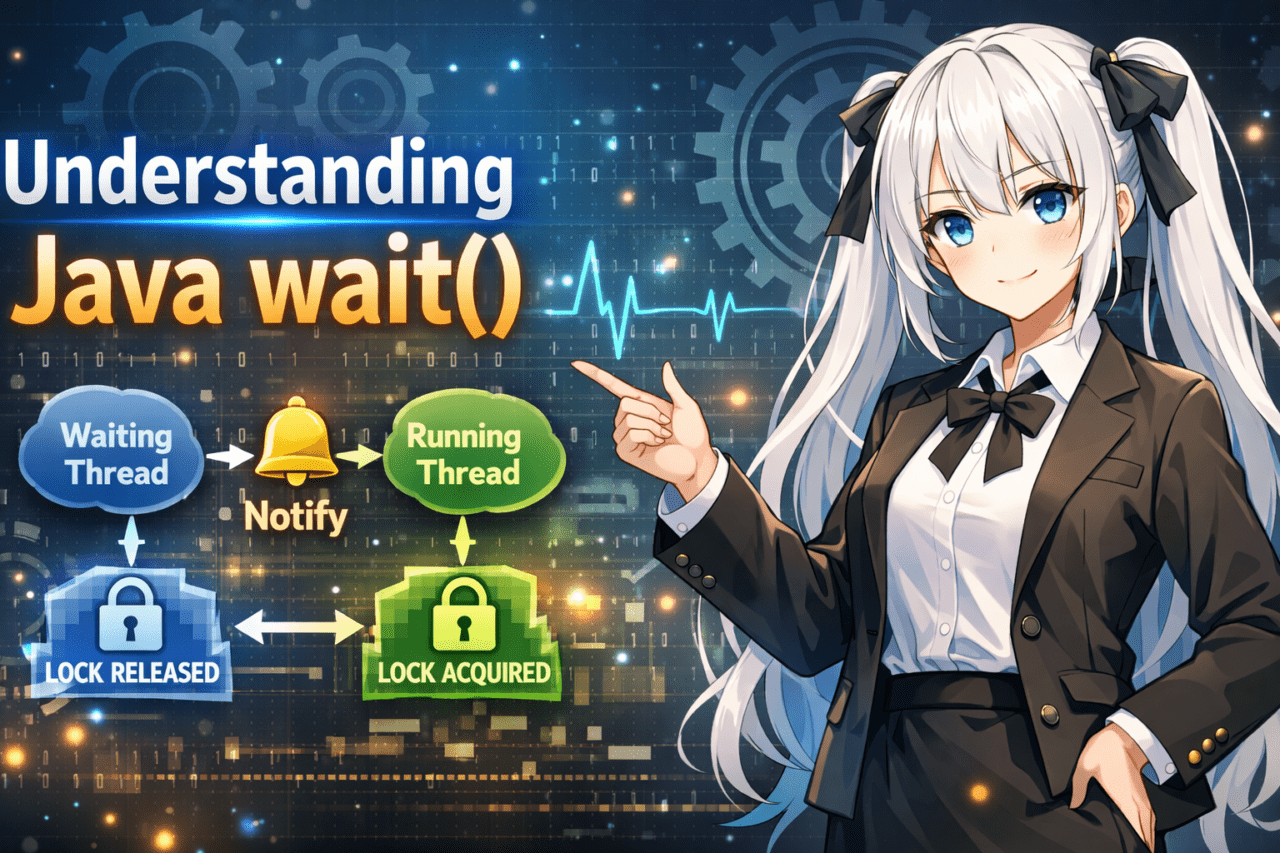

1.1 The Basic Meaning of wait()

The essence of wait() comes down to these three points:

- Put the current thread into a waiting state

- Temporarily release the lock of the target object

- Resume when notified by another thread

Conceptual flow:

- Enter a

synchronizedblock - Call

wait() - Release the lock and enter the waiting state

- Another thread calls

notify() - Re‑acquire the lock, then resume execution

Simple syntax example:

synchronized(obj) {

obj.wait();

}

⚠ Note

wait()is not “pause for a fixed time,” but “wait for a notification.”- If no one notifies, it can wait forever.

1.2 wait() Is a Method of Object

wait() is not a method of Thread.

It’s a method of Object.

Definition (concept):

public final void wait()

In other words:

- Every Java object has

wait() - You wait based on the object you’re monitoring

Common misconceptions:

❌ Thinking it’s Thread.wait()

❌ Thinking it directly “stops a thread”

Correct understanding:

✔ “Wait on an object’s monitor (monitor lock)”

*Monitor = the lock managed by synchronized.

1.3 Mandatory Requirement to Use wait()

To use wait(), you must call it inside a synchronized block.

Why:

wait()releases the lock that you currently hold- If you don’t hold the lock, consistency cannot be guaranteed

Incorrect example:

Object obj = new Object();

obj.wait(); // ❌ IllegalMonitorStateException

Correct example:

Object obj = new Object();

synchronized(obj) {

obj.wait();

}

Exception thrown:

IllegalMonitorStateException

This means “wait() was called without holding the lock.”

⚠ Where Beginners Often Get Stuck

- Confusing it with

sleep()(sleep does not release the lock) - Forgetting to write

synchronized - Never calling

notify, so it stops forever - Calling

notifyon a different object

✔ Most Important Summary So Far

wait()is a method ofObject- It can only be used inside

synchronized - It releases the lock and waits for a notification

- It is not a simple “time delay”

2. Correct Usage of wait() (Understand with Code Examples)

wait() does not make sense by itself.

It only works when combined with notify / notifyAll.

In this chapter, we’ll explain it step‑by‑step, from the minimum setup to practical patterns.

2.1 Basic Syntax

The smallest correct structure looks like this:

Object lock = new Object();

synchronized(lock) {

lock.wait();

}

However, this will stop forever as‑is.

Reason: there is no notification (notify).

2.2 Example with notify (Most Important)

wait() means “wait for a notification.”

Therefore, another thread must call notify.

✔ Minimal Working Example

class Example {

private static final Object lock = new Object();

public static void main(String[] args) {

Thread waitingThread = new Thread(() -> {

synchronized(lock) {

try {

System.out.println("Waiting...");

lock.wait();

System.out.println("Resumed.");

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

});

Thread notifyingThread = new Thread(() -> {

synchronized(lock) {

System.out.println("Notifying...");

lock.notify();

}

});

waitingThread.start();

notifyingThread.start();

}

}

Execution Flow

waitingThreadacquireslock- It calls

wait(), releases the lock, and waits notifyingThreadacquireslock- It calls

notify()to signal the waiting thread - After re-acquiring the lock, execution resumes

2.3 Difference Between notify and notifyAll

| Method | Behavior |

|---|---|

| notify() | Resumes only one waiting thread |

| notifyAll() | Resumes all waiting threads |

In real-world code, notifyAll() is often considered safer.

Why:

- With

notify(), a thread that should not resume might be selected - When multiple conditions exist, inconsistencies become more likely

2.4 The Correct Practical Pattern (Use while)

wait() is typically used together with a condition check.

synchronized(lock) {

while (!condition) {

lock.wait();

}

}

Why:

- Spurious wakeups (resuming without notification) can happen

- After

notifyAll, the condition may still not be satisfied

❌ Incorrect example:

if (!condition) {

lock.wait();

}

This is not safe.

⚠ Common Mistakes

- Calling

waitandnotifyon different objects - Assuming it resumes immediately after

notify(it must re-acquire the lock) - Calling

notifyoutsidesynchronized - Forgetting to update the condition variable

✔ Implementation Steps Summary

- Create a shared lock object

- Wrap with

synchronized - Check the condition with

while - Wait with

wait() - Notify from another thread using

notify/notifyAll - Always update the condition

3. The Difference Between wait and sleep (The Core Search Intent)

Many users who search for “java wait” want to understand how it differs from sleep().

They may look similar, but their design philosophy and use cases are completely different.

3.1 The Decisive Differences (Comparison Table)

| Item | wait | sleep |

|---|---|---|

| Defined in | Object | Thread |

| Releases lock | Yes | No |

| Where to use | Must be inside synchronized | Can be used anywhere |

| Purpose | Inter-thread communication | Simple time delay |

3.2 The Biggest Difference: “Does It Release the Lock?”

✔ How wait Behaves

- Releases the lock currently held

- Allows other threads to acquire the lock

- Resumes via

notifysynchronized(lock) { lock.wait(); }

✔ How sleep Behaves

- Stops while still holding the lock

- Other threads cannot acquire the lock

Thread.sleep(1000);

⚠ This is the most important point

sleep = “wait for time”

wait = “wait for a notification”

3.3 How to Choose in Real-World Work

✔ When to Use wait

- Producer/Consumer patterns

- Waiting for data to arrive

- Waiting for a state change

- Coordinated control between threads

✔ When to Use sleep

- Simple delay processing

- Adjusting retry intervals

- Waiting in test code

3.4 Using wait with a Timeout

wait can also be called with a timeout.

lock.wait(1000); // Wait up to 1 second

But note:

- It may return after the timeout, but there is no guarantee the condition is satisfied

- You must re-check the condition using

while

⚠ Points That Confuse Beginners

- Thinking

sleepresumes via notification → ❌ - Thinking

waitalways resumes after time → ❌ - Thinking locks are released during

sleep→ ❌

✔ Conclusion

sleepis just a time delaywaitis a mechanism for inter-thread communication- The biggest difference is whether the lock is released

4. Advanced wait Knowledge (Must-Know for Safe Usage)

wait looks simple, but misuse can easily cause bugs.

Here we’ll explain the essential knowledge needed to implement it safely.

4.1 wait with a Timeout

wait has a timed version.

synchronized(lock) {

lock.wait(1000); // Wait up to 1 second

}

Behavior:

- Waits up to the specified time

- Returns immediately if notified

- May also return when the time expires

⚠ Important

Even if it returns due to timeout, it does not mean “the condition is true.”

Always combine it with a condition check.

4.2 What Is a Spurious Wakeup?

A spurious wakeup (Spurious Wakeup) is a phenomenon where

wait may return even without a notification.

The Java specification allows this to happen.

That means:

- No one called

notify - The condition hasn’t changed

- Yet it may still return

That’s why using while instead of if is mandatory.

4.3 The Correct Pattern (Wrap with while)

Correct implementation example:

synchronized(lock) {

while (!condition) {

lock.wait();

}

// Code after the condition becomes true

}

Why:

- Protection against spurious wakeups

- The condition may still be false after

notifyAll - Safety when multiple threads are waiting

❌ Dangerous example:

synchronized(lock) {

if (!condition) {

lock.wait(); // Dangerous

}

}

This style can lead to incorrect behavior.

4.4 Relationship with Deadlocks

wait releases a lock, but

deadlocks can still happen when multiple locks are involved.

Example:

- Thread A → lock1 → lock2

- Thread B → lock2 → lock1

Mitigations:

- Use a consistent lock acquisition order

- Minimize the number of locks

⚠ Common Critical Mistakes

- Not updating the condition variable

- Calling

notifywithout changing state - Nesting

synchronizedtoo much - Not keeping lock order consistent across multiple locks

✔ Advanced Summary

- Wrapping

waitwithwhileis an absolute rule - Even with timeouts, you must re‑check the condition

- Poor lock design can cause deadlocks

5. Common Errors and How to Fix Them

wait is a low‑level API, so implementation mistakes directly cause bugs.

Here we’ll summarize common errors, their causes, and how to fix them.

5.1 IllegalMonitorStateException

This is the most common error.

When it happens:

- Calling

waitoutsidesynchronized - Calling

notifyoutsidesynchronized

❌ Incorrect example

Object lock = new Object();

lock.wait(); // Exception thrown

✔ Correct example

synchronized(lock) {

lock.wait();

}

Fix summary:

- Always call

wait/notifyinsidesynchronizedon the same object - Use one consistent lock object

5.2 It Doesn’t Resume Even After notify

Common causes:

- Calling

notifyon a different object - The condition variable isn’t updated

- Holding the lock too long after

notify

❌ Typical mistake

synchronized(lock1) {

lock1.wait();

}

synchronized(lock2) {

lock2.notify(); // Different object

}

✔ Always use the same object

synchronized(lock) {

lock.wait();

}

synchronized(lock) {

condition = true;

lock.notifyAll();

}

5.3 wait Never Ends

Main causes:

notifyis never called- Incorrect condition‑check logic

- The

whilecondition stays true forever

Debug steps:

- Confirm that

notifyis definitely being called - Confirm that the condition variable is being updated

- Use logs to trace thread execution order

5.4 Deadlocks

Typical pattern:

synchronized(lock1) {

synchronized(lock2) {

...

}

}

If another thread acquires locks in the opposite order, the program can freeze.

Mitigations:

- Use a consistent lock acquisition order

- Use a single lock if possible

- Consider using

java.util.concurrent

5.5 Handling InterruptedException

wait throws InterruptedException.

try {

lock.wait();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

Thread.currentThread().interrupt();

}

Recommended handling:

- Restore the interrupt flag (re‑interrupt)

- Don’t swallow the exception

⚠ Very Common Mistakes in Practice

- Wrapping

waitwithif - Calling

notifybefore updating the condition - Managing multiple locks ambiguously

- Using an empty

catchblock

✔ Core Rules to Avoid Errors

synchronizedis required- Use the same lock object consistently

- Always use the

whilepattern - Update state before calling

notify - Handle interrupts properly

6. Modern Alternatives in Java (Practical Perspective)

wait / notify are low‑level thread coordination tools that have existed since early Java.

In modern real‑world development, it’s common to use safer, higher‑level APIs instead.

In this chapter, we’ll summarize why alternatives are recommended.

6.1 wait/notify Are Low‑Level APIs

When you use wait, you must manually manage everything yourself.

Things you must manage:

- Lock control

- Condition variables

- Notification order

- Protection against spurious wakeups

- Deadlock avoidance

- Interrupt handling

In other words, it’s a design that easily becomes a breeding ground for bugs.

It becomes dramatically more complex when multiple conditions and multiple threads are involved.

6.2 Common Alternative Classes

Since Java 5, the java.util.concurrent package has been available.

✔ BlockingQueue

For passing data between threads.

BlockingQueue<String> queue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<>();

queue.put("data"); // Waiting is handled automatically

queue.take(); // Waits until data arrives

Characteristics:

- No need for

wait/notify - Less likely to cause deadlocks

- Very commonly used in real‑world systems

✔ CountDownLatch

Waits for multiple threads to complete.

CountDownLatch latch = new CountDownLatch(1);

latch.await(); // Wait

latch.countDown(); // Signal

Use cases:

- Waiting for initialization to complete

- Synchronizing parallel tasks

✔ ReentrantLock + Condition

An API that provides a mechanism similar to wait, but more explicitly.

ReentrantLock lock = new ReentrantLock();

Condition condition = lock.newCondition();

lock.lock();

try {

condition.await();

} finally {

lock.unlock();

}

Benefits:

- Can manage multiple conditions

- More flexible lock control

6.3 What Should You Use in Practice?

Recommendations by scenario:

| Goal | Recommended Tool |

|---|---|

| Passing data | BlockingQueue |

| Simple synchronization | CountDownLatch |

| Complex condition control | ReentrantLock + Condition |

| Learning | Understanding wait is essential |

Conclusion:

- It’s important to understand

waitwhile learning - In practice, prefer the

concurrentpackage

⚠ Practical Decision Criteria

- Do you really need to implement thread coordination yourself?

- Can the standard library solve it instead?

- Can you ensure readability and maintainability?

In many cases, you can solve the problem without using wait.

✔ Chapter Summary

waitis a low‑level API- The

concurrentpackage is the modern standard - Prioritize safety in real‑world code

7. Summary (Final Notes for Beginners)

java wait is a mechanism used to wait for state changes between threads.

The most important point is that it’s not a simple time delay, but a “notification‑based control mechanism.”

Let’s summarize what we covered from an implementation perspective.

7.1 The Essence of wait

- A method of

Object - Can only be used inside

synchronized - Releases the lock and waits when called

- Resumes via

notify/notifyAll

7.2 Three Rules for Writing Safe Code

1) Always use synchronized

2) Wrap with while

3) Update state before calling notify

Correct template:

synchronized(lock) {

while (!condition) {

lock.wait();

}

}

Notifier side:

synchronized(lock) {

condition = true;

lock.notifyAll();

}

7.3 The Decisive Difference from sleep

| Item | wait | sleep |

|---|---|---|

| Releases lock | Yes | No |

| Use case | Inter-thread communication | Time delay |

It’s important not to confuse them.

7.4 Where It Fits in Real‑World Development

- Understanding it is essential

- But in practice, prioritize the

concurrentpackage - Design custom

wait‑based control very carefully

7.5 Final Checklist

- Are you using the same lock object?

- Are you calling it inside

synchronized? - Is it wrapped with

while? - Do you update state before

notify? - Are you handling interrupts properly?

If you follow these, you can reduce the risk of serious bugs significantly.

FAQ

Q1. Is wait a method of the Thread class?

No. It is a method of the Object class.

Q2. Can I use wait without synchronized?

No. It will throw IllegalMonitorStateException.

Q3. Which should I use: notify or notifyAll?

If you prioritize safety, notifyAll is recommended.

Q4. Can wait be used with a timeout?

Yes. Use wait(long millis).

Q5. Why use while instead of if?

To protect against spurious wakeups and returning before the condition is satisfied.

Q6. Is wait commonly used in modern production code?

In recent years, using java.util.concurrent has become the mainstream approach.

Q7. Can I replace it with sleep?

No. sleep does not release the lock.